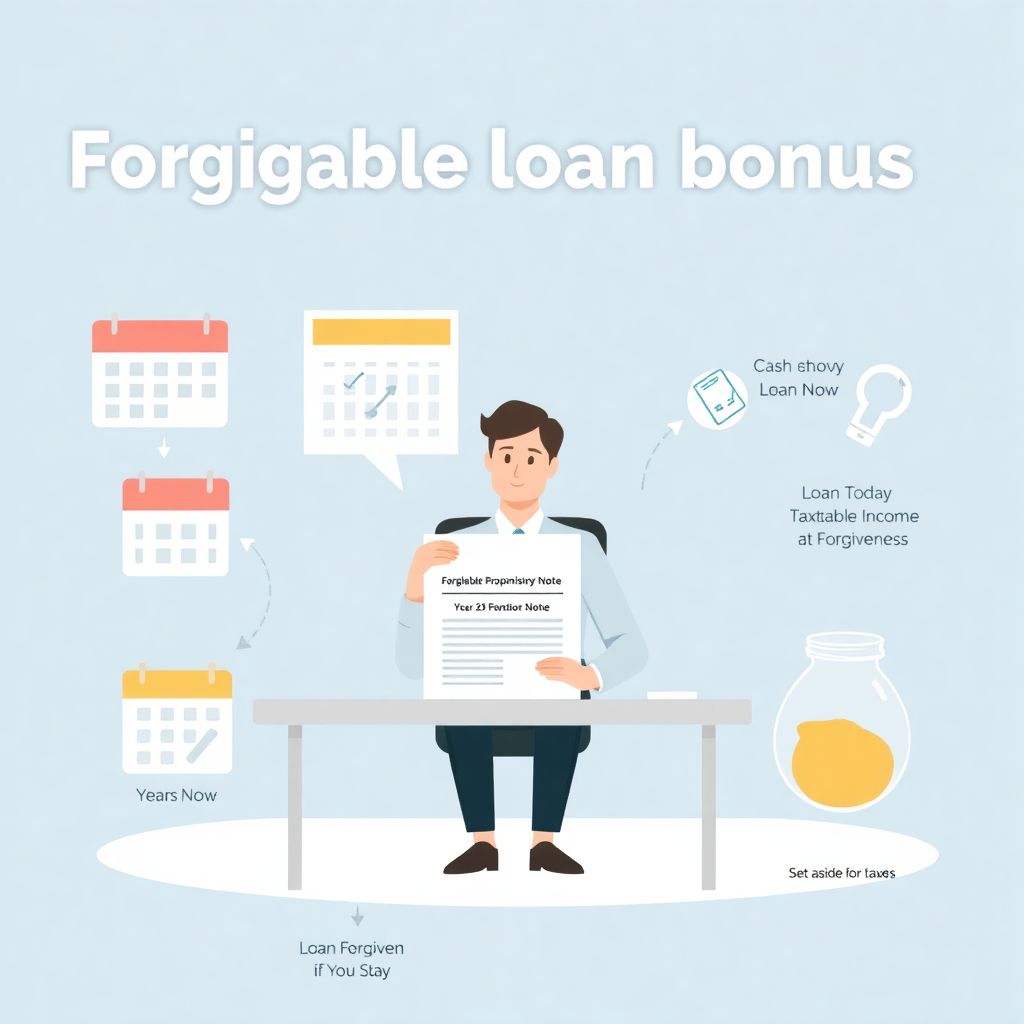

Received a “bonus” as a forgivable loan with no tax withholding: what does it really mean?

What you’ve been given is not a traditional cash bonus. It’s a forgivable promissory note – essentially a loan that will be erased if you meet certain conditions, usually staying with the company for a set number of years.

From a tax standpoint, that structure changes the *timing* and *mechanics* of how you owe tax, but it usually doesn’t change the core fact:

this is compensation for your work and is taxable income.

Below is how this typically works in the US and what you should consider doing with the money.

—

1. What is a forgivable promissory note bonus?

Instead of paying a regular cash bonus and withholding taxes immediately, your employer:

– Issues you a loan (the note) for a large lump sum.

– Promises to forgive this loan if you remain employed for a specified period (for example, three years).

– If you leave early, you may have to repay some or all of the note.

From the company’s perspective, this structure acts as a retention tool and can also shift when withholding is handled. But for you, it is still pay for services.

—

2. When is it taxable – now or later?

In most cases, the taxable event happens when the loan (or the relevant portion of it) is forgiven, not when you first receive the cash.

Common patterns:

– Cliff forgiveness:

If the note is fully forgiven after three years, then in the year it is forgiven, the entire forgiven amount is treated as taxable wages.

– Graded forgiveness:

If the note is forgiven ratably (for example, 1/3 per year over three years), each year’s forgiven portion is taxed as income in that year.

The exact structure should be spelled out in the agreement you signed. That document is key.

—

3. Will it show up on your W‑2?

Yes, in almost all cases it eventually shows up on your W‑2 as wages.

Typical scenario:

– In the year(s) when forgiveness occurs, your employer reports the forgiven amount as taxable compensation.

– That amount appears in your W‑2 wages for that year and is subject to income tax, Social Security, and Medicare (up to the relevant wage caps).

If the entire note is forgiven in year three, then year three’s W‑2 might suddenly show an extra several hundred thousand dollars of income, even though the cash hit your bank account years earlier.

That’s why this can cause nasty surprises for people who have already spent the money.

—

4. What about tax withholding?

The fact that no taxes were withheld when you received the lump sum is not unusual for these structures, but it does not mean the money is tax‑free.

Two common approaches:

1. No withholding now, withholding at forgiveness

When the note is forgiven, your employer processes that amount through payroll as taxable wages and withholds taxes then.

2. Under‑withholding risk

Even if your employer withholds at forgiveness, the amount withheld may be based on supplemental wage rules (often a flat percentage), which may be lower than your effective tax rate on such a large one‑time income spike.

That means you may still owe additional tax when you file, especially if the forgiven amount pushes you into a higher bracket.

—

5. Should you set aside part of the money?

Yes. With a large, unforgiven “bonus loan,” a conservative move is to treat a substantial portion as not really yours yet.

Practical approach:

– Assume this will be fully taxable at your marginal tax rate in the year(s) it is forgiven.

– For a high earner, it’s often reasonable to plan on at least:

– Federal tax at your top bracket (for many people, 32–37%).

– State and local taxes, if applicable.

– Payroll taxes (Social Security and Medicare), at least on the portion still under the Social Security wage base.

Because you mentioned “several hundred thousand dollars,” the forgiveness could easily push you into one of the highest brackets, especially in the year it hits your W‑2.

That’s why keeping a large chunk in a liquid account or short‑term, low‑risk asset is wise. You don’t want to be scrambling to come up with six figures of tax because you treated the entire deposit as “spendable” money.

—

6. How much is “enough” to stash?

You’ll want to run a rough estimate tailored to your situation, but as a simple framework:

1. Estimate your future marginal federal tax bracket in the year of forgiveness (look at your current income and add the forgiven amount).

2. Add your state tax rate if you live in an income‑tax state.

3. Consider the payroll tax effect:

– Social Security: only up to the annual wage cap, and only once per year.

– Medicare: no wage cap; plus possible additional Medicare surtax at higher incomes.

For a high‑income professional in a state with income tax, a very rough ballpark is often 40–50% total on that incremental income. It’s not exact, but it’s safer to over‑save than under‑save.

If that feels too conservative, you can tighten the estimate using last year’s return and current salary numbers.

—

7. What happens if you leave before the three years?

This is crucial, and many people overlook it.

If you terminate employment before the note is fully forgiven, typically:

– You are required to repay the unforgiven portion of the note.

– You generally don’t owe income tax on any part that was never forgiven (because it never became income).

But watch out for:

– If part of the note has already been forgiven and taxed in prior years, you may not get to “undo” that income just because you reimbursed the company.

– The contract should explain the exact rules for repayment, interest, and any acceleration in different termination scenarios (voluntary resignation, layoff, termination for cause, etc.).

Before making major life or job decisions, you want to know precisely how much you’d owe back if you left.

—

8. Are there any interest or imputed interest issues?

Some notes are structured with little or no stated interest. In certain cases, tax rules can treat a low‑interest or no‑interest loan as if interest exists, creating imputed interest income or other complexities.

Often, large corporate retention loans are drafted to comply with these rules, but you should still:

– Check your agreement for the stated interest rate, if any.

– Ask whether any imputed interest or similar tax reporting is expected.

This is more of a nuance, but for very large sums, even small technicalities can matter.

—

9. Planning strategies to avoid a tax shock

To manage this well:

1. Read the promissory note carefully

– How and when is the loan forgiven?

– What happens if you’re fired, laid off, or resign?

– Is there any clawback if you leave shortly after forgiveness?

2. Talk to HR or payroll (in writing if possible)

– Ask when they expect to report the forgiveness as income.

– Ask when they plan to withhold taxes, and at what approximate rate.

3. Meet with a tax professional

Given the size of the bonus, paying for an hour or two with a CPA or tax attorney is usually well worth it.

Bring:

– Your promissory note and any related correspondence.

– Recent pay stubs and last year’s tax return.

– Any equity compensation or other large income items that might intersect with this.

4. Set aside cash now

– Keep a significant portion of the funds in a high‑liquidity, low‑risk vehicle: high‑yield savings, money market, short‑term Treasury instruments.

– Treat that portion as “reserved for future tax and possible repayment” until the loan is fully forgiven and you know your exact bill.

5. Consider timing of other income

– If forgiveness is scheduled in a year when you also have major stock vesting, business income, or asset sales, it can stack together in an especially painful way.

– Sometimes, when you have flexibility, shifting other income or deductions across years can soften the blow.

—

10. Will this affect estimated taxes?

If forgiveness happens partway through a year and withholdings are inadequate, you might:

– Need to make estimated tax payments during that year to avoid penalties for underpayment.

– Or adjust your regular withholding on your normal salary to account for the extra income.

This is another reason to proactively involve a tax professional once you know the forgiveness timeline. Large, irregular income often triggers the “you owe a penalty because you didn’t pay enough tax during the year” problem if you don’t plan ahead.

—

11. Psychological trap: it feels like “free money”

It’s easy to view this as a giant windfall and mentally spend it. But in reality:

– A significant slice likely belongs to the IRS and your state at some future date.

– Another slice is contingent on staying employed under certain conditions.

– Only the remainder is truly yours.

Thinking of the tax portion as a temporary escrow can help: you’re just holding the government’s cut for a while.

—

12. Key takeaways

– A forgivable promissory note used as a retention bonus is, economically, taxable compensation, just packaged as a loan.

– It is generally taxable when forgiven, not when first received.

– The forgiven amount will almost certainly be reported as wages on your W‑2 in the year(s) of forgiveness.

– Because no tax was withheld upfront, you should proactively reserve a large share of the money in a liquid, low‑risk place to cover future tax and any potential repayment.

– Carefully read your agreement, clarify details with HR/payroll, and consult a tax professional to model your actual tax hit and avoid surprises.

If you treat this as partially “not yours yet” and plan around the timing of forgiveness, you can enjoy the benefit of the retention bonus without ending up in a cash crunch when the tax bill finally arrives.