Planning for long-term care sounds theoretical until a parent falls, gets a diagnosis, or simply starts forgetting to turn off the stove. Then it becomes very real, very fast. Families usually discover that “we’ll manage somehow” isn’t a plan. You need to know what help exists, what it costs, who pays, and how to keep your relatives safe without burning out or going broke yourself. This guide walks through the main options, compares different strategies, and gives you numbers to ground the conversation, not scare you into it.

Why planning for long-term care can’t wait

Most families underestimate both how likely long-term care is and how much it costs. In the US, about 70% of people over 65 will need some form of long-term care, often for several years. It’s not just nursing homes: it can be help with bathing, dressing, meals, or supervision for dementia. The catch is that Medicare covers only short-term rehabilitation, not ongoing custodial help. Without a plan, children scramble to juggle jobs, kids, and care, arguing over money and decisions under pressure instead of calmly choosing what makes sense.

Step one: clarify needs and family capacity

Before arguing about money or facilities, map out what your loved one actually needs and what the family can realistically provide. Look at activities of daily living: can they bathe, dress, use the toilet, move around, eat, manage medications? A parent may insist they’re “fine,” but you’re seeing unpaid bills, a dirty fridge, or new dents in the car. At the same time, ask siblings what they can contribute in time and cash. A daughter living nearby may do daily check-ins, but it’s unfair to assume she’ll provide full-time care if she’s also working and raising kids.

> Technical note: Standard assessment tools

> Professionals often use ADL (Activities of Daily Living) and IADL (Instrumental ADLs) checklists. Needing help with 2+ ADLs is a common trigger for long term care insurance plans for families to start paying benefits, so documenting this properly can be crucial for claims.

Option 1: Family caregiving as the main solution

Many families start with, “We’ll take care of mom ourselves.” This approach can work well early on, especially if needs are light and relatives live close. It preserves independence and taps into existing trust. But there are hidden costs: unpaid caregivers in the US provide care worth an estimated hundreds of billions annually, and many cut their work hours or leave jobs entirely. Over time, chronic stress, back injuries from lifting, and emotional exhaustion are common. The care may be “free” on paper, but the caregiver’s lost income and health impact can be enormous, so it’s essential to be honest about long-term sustainability.

Option 2: In‑home care and “aging in place”

A more balanced approach is to combine family help with in home long term care services for seniors. A home health aide might come a few hours a day to help with bathing, meals, and safety checks, while family handles companionship, rides, and overseeing finances. This can significantly delay or even avoid a move to a facility. In the US, non-medical home care often runs between $25 and $35 an hour; even 20 hours a week adds up quickly. Still, for many people this feels like the least disruptive and most dignified solution, especially for elders strongly attached to their home and neighborhood.

> Technical note: Cost comparison baseline

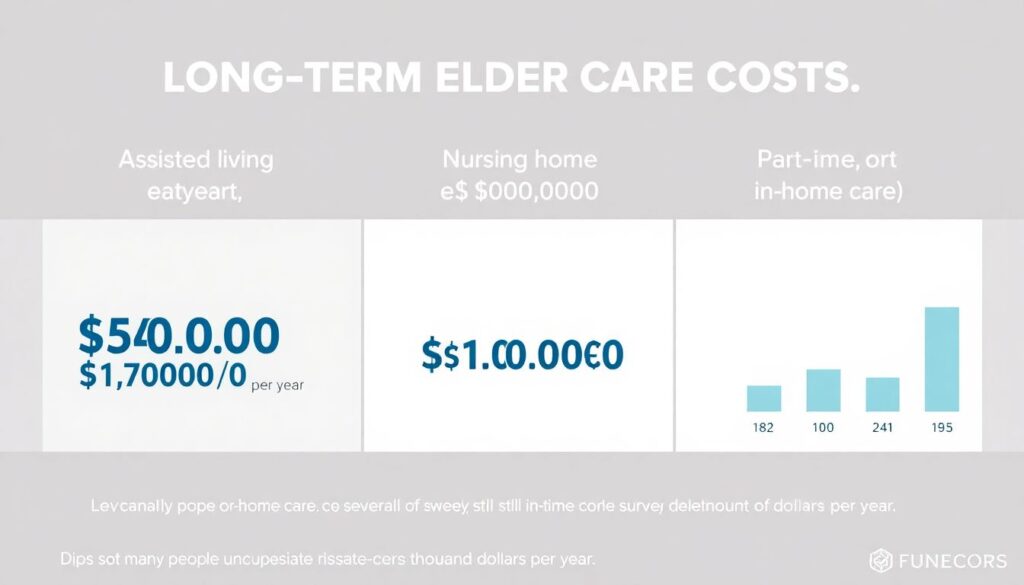

> If you pay $30/hour for 20 hours weekly, that’s about $2,400 per month. Compare that to assisted living, which averages around $4,500–$6,000 per month nationally, and nursing homes, which can exceed $9,000 monthly for a private room. These ranges matter when you estimate the cost of long term care for elderly parents over several years.

Option 3: Assisted living and nursing facilities

At some point, safety and medical complexity may push the discussion toward residential care. Families often Google “best long term care facilities near me” in a panic after a hospitalization. Assisted living works well for people who need help with daily tasks but not intensive medical care. Memory care units add secure environments and specialized dementia support. Nursing homes provide round-the-clock skilled care. The upside is professional staffing and built‑in structure; the downside is cost, adjustment stress, and variable quality. It’s crucial to visit multiple places, talk to families in the lobby, and go unannounced at different times of day before making a decision.

Comparing home care vs facility care: what really differs

When you compare home-based and facility-based care, three factors dominate: control, cost, and social life. At home, you control routines and environment; in facilities, you share schedules and staff. Home care can be cheaper at low to moderate hours but may surpass facility costs if 24/7 coverage is needed. Socially, facilities can offer activities, but in practice some residents stay isolated in their rooms. At home, isolation is also a risk unless you deliberately plan visits and community engagement. There is no universal “best” solution; it’s a trade‑off between safety, independence, and finances that looks different for every family.

> Technical note: When 24/7 home care stops making sense

> Around‑the‑clock home care usually means three 8‑hour shifts. At $28/hour, that’s about $20,000+ per month, far higher than most nursing homes. For advanced dementia or severe mobility issues, a facility may be both safer and financially more rational, even if emotionally harder to accept.

The money question: what does long‑term care really cost?

Many people guess low by tens of thousands per year. To ground the discussion, look at national or state cost surveys from reputable sources. For illustration: a year of assisted living might run $60,000–$70,000, nursing home care can top $100,000 annually, and a few days a week of home care can still cost $20,000–$30,000 a year. Multiply by three to five years of need, and you’re easily into six‑figure territory. Understanding the true cost of long term care for elderly parents is uncomfortable but vital; only then can you decide whether savings, insurance, government programs, or a mix will realistically carry the load.

Long‑term care insurance: who it helps and when

Long term care insurance plans for families are designed to cover some of these expenses, but they’re not a fit for everyone. Premiums are lower when bought in your 50s or early 60s, before health issues appear. Policies typically pay a daily or monthly benefit once you can’t perform a certain number of ADLs or have cognitive impairment. The catch is affordability and complexity: premiums can rise, and some policies come with strict waiting periods or benefit caps. Still, for middle‑income households with assets to protect but not enough to self‑fund care, insurance can be the difference between controlled choices and crisis‑driven decisions.

> Technical note: Comparing insurance options

> When you compare long term care insurance quotes online, watch four levers: (1) daily or monthly benefit, (2) benefit period in years, (3) elimination period before payments start, and (4) inflation protection. A 3% compound inflation rider may significantly raise premiums but helps benefits keep pace with rising care costs over decades.

Hybrid policies and self‑funding strategies

In recent years, hybrid life insurance with long‑term care riders has gained ground. You pay higher premiums, but if you never need care, your heirs receive a death benefit; if you do need care, you draw down that benefit. This can feel psychologically easier than “use it or lose it” coverage. For high earners or those with significant savings, self‑funding is another approach: earmark investment accounts specifically for future long-term care, sometimes via tax‑advantaged vehicles where available. The risk here is misjudging how much you’ll need or that market downturns hit just as care costs spike, so running projections with a planner is wise.

Government programs: Medicaid, not Medicare, is the key

A common misconception is that Medicare pays for long‑term custodial care; it doesn’t. It covers short rehab after hospital stays, not ongoing help with bathing or dementia supervision. Medicaid, on the other hand, does cover long-term care for those with low income and limited assets, but qualification rules are strict. People sometimes “spend down” assets to qualify, but there are look‑back periods (often 5 years in the US) that penalize certain transfers. Some states also fund home‑ and community‑based services under Medicaid waivers, which can help people stay at home instead of entering a nursing home.

> Technical note: Asset protection considerations

> Legal tools like irrevocable trusts, spousal refusal strategies, and carefully timed gifting can sometimes protect a portion of assets while still aiming for future Medicaid eligibility. These are highly jurisdiction‑specific and should only be set up with an elder law attorney who understands local rules and look‑back penalties.

Practical planning sequence for families

1. Clarify medical status and likely prognosis with the primary doctor or specialist.

2. List current and expected care needs over the next one to five years.

3. Inventory income, savings, insurance, and housing options.

4. Explore in-home, community, and facility options; visit and interview providers.

5. Decide on a primary plan (e.g., home with supports) and a backup if needs escalate.

6. Formalize financial and legal documents: powers of attorney, health care proxy, and updated wills.

7. Revisit the plan annually or after any major health change, adjusting as needed.

Balancing fairness between siblings

Family politics can make or break even the most rational plan. One sibling may live nearby, another far away; one earns more, another has more free time. Instead of resentment simmering under the surface, spell out roles. The local sibling might handle doctor visits and day‑to‑day oversight, while the distant one contributes more financially or manages paperwork and insurance claims. If a child reduces work hours to care for a parent, consider a written caregiver agreement that pays them from the parent’s funds, transparent to all siblings, to avoid future accusations of unfairness or “hidden” transfers.

Using the internet without drowning in information

Online research is both a blessing and a trap. It’s easy to lose hours scrolling through options for in home long term care services for seniors or scanning reviews of facilities. Use the web strategically: search your state’s eldercare directory, look at inspection reports, and then call a short list of providers. When you search for phrases like “best long term care facilities near me,” treat star ratings as a starting point, not gospel. A glowing review may reflect one great nurse on one good day; consistent patterns in complaints are usually more revealing about long‑term quality and staffing.

Emotional side: preparing the family conversation

Talking to parents about long‑term care can feel like walking into a minefield. Many fear losing control more than they fear illness itself. Instead of leading with, “We need to put you in a home,” start with concerns you share: “We want you safe and able to make your own choices as long as possible; can we talk about what you’d want if walking or memory gets harder?” Framing the discussion around honoring their preferences usually goes better. Expect multiple conversations, not one decisive meeting, and allow everyone time to digest and adjust emotionally.

When to get professional help

If the situation is complex—multiple chronic conditions, limited savings, possible Medicaid, and sibling disagreements—bringing in professionals can actually save money and stress. Elder law attorneys, geriatric care managers, and fee‑only financial planners who specialize in aging issues can help you build a realistic roadmap. They know local costs, typical pitfalls, and which resources your family tends to overlook. Their fees may sting up front, but compared to making a rushed, expensive choice about care that doesn’t fit, a few hours of expert guidance can be a very high‑value investment in everyone’s sanity.

Pulling it together: choosing a path that fits your family

In the end, planning for long‑term care is less about finding a perfect solution and more about choosing trade‑offs deliberately. Some families lean heavily on home care, supplementing with part‑time aides; others prioritize professional facilities and focus their energy on visits and advocacy. Insurance may carry part of the load, or you might mix savings, home equity, and selective use of government programs. What matters is that the plan is written down, shared, financially plausible, and emotionally acceptable enough that people will actually follow it. Start while stakes are lower, adjust as reality unfolds, and keep the conversation going.